|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. THE NEW YORK TIMESEddie Palmieri, Latin-Music Patriarch, Stays HungryBy BEN RATLIFF

April 30, 2002

Eddie Palmieri at Woolsey Hall at Yale after receiving a Chubb Fellowship. ---------- Among the many theories held by the Latin-music bandleader, pianist and ideologue Eddie Palmieri, is this: the less you eat, the more power you have. "See, we're essentially an air-gas engine," he said. "The less encumbrance in the organism, the more vitality." So at a lunch meeting this month, Mr. Palmieri – who is a trim and voluble 65 – forswore food, asked for rum on the rocks and began a hurricane of talk. He revealed his preoccupations one by one, in quick succession, as if laying them around himself in a circle. He had a sore wrist, and he talked about hand muscles: decades of playing octaves in both hands to make his piano ring over brass and percussion sections have left his three middle fingers underdeveloped, he said; he has taken up exercises to make them more independently agile. He talked about aging, which he prefers to call "extending maturity and resisting decline." Yet Mr. Palmieri, who was born in Harlem of Puerto Rican parents is, despite his resistance, a grand old man of culture and is about to be celebrated as such by a Chubb Fellowship at Yale University, an honor usually given to statesmen and ex-presidents. He talked about the construction of arrangements played by the great Cuban conjuntos of the 1950's – which at one time he studied rigorously on 45 and 78 r.p.m. records – as if they were gleaming suspension bridges. He talked about his heroes, who include the music theorist Joseph Schillinger, the philosopher Spinoza, the jazz pianist Thelonious Monk, and his own reclusive guru during the 70's and 80's, the singer Bob Bianco. And he talked about the Palladium, at 53rd Street and Broadway, the great palace of New York mambo culture in the 1950's and 60's, where he played until the club's closing in May 1966, and where he was allowed to polish a jewel of a band that has yielded new dividends for him.

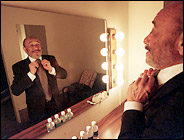

Mr. Palmieri before the show. ---------- With Tito Puente's death last year, Mr. Palmieri is the patriarch of Latin music in the United States. And during a commercially and aesthetically terrible time for salsa, the genre that he helped create, Mr. Palmieri is flourishing. Recently he has unpacked the old music played by his band, Conjunto La Perfecta, an important group that during its existence (1961-68) prefigured much of the Latin music to come in the next three decades. La Perfecta had a hard, raw sound, with two and sometimes three trombones in the front line; it reacted against the plushness of the Afro-Cuban jazz orchestras, as well as the courtliness of the violin-and-flutes charanga sound. It was a band that incorporated improvisation deeply into its structure. "Cuban music is based on repetition," said the trumpeter Brian Lynch, who has played with Mr. Palmieri for 15 years. "And jazz is based on variation. So if you marry those two together, you get La Perfecta, in which you have riffs, but you're always doing something to the riff as you repeat it." Mr. Palmieri likes to move forward. First with La Perfecta he changed the instrumentation of the Latin dance orchestra. Then he changed the recording format, breaking the three-and-a-half-minute barrier with his broadly popular eight-and-a-half-minute hit "Azúcar" in 1965. Then jazz came into his life, through listening to pianists as diverse as Monk, Dick Twardzik, Bill Evans and especially McCoy Tyner; he became serious about superimposing jazz harmony over Afro-Caribbean rhythm. And in the early 70's he made an influential Latin funk record, "Harlem River Drive." Like Miles Davis, another of his heroes, he doesn't feel good about doing what he was doing five years ago. So he had set aside La Perfecta's tunes like "Cuídate Compay," "El Molestoso" and "Tirándote Flores" for more than 30 years, feeling that they were of their moment and better left alone. But he has been playing them again over the last few months, with a slightly altered version of the original La Perfecta instrumentation; and some of the music has been revived for a remarkably strong new recording, "La Perfecta II," which was released last week on Concord records. (Mr. Palmieri and La Perfecta II will play a JVC Jazz Festival concert on June 29 at Carnegie Hall.) "At the Palladium, Wednesday was the American crowd," he remembered. "You'd see Marlon Brando and Kim Novak. Killer Joe Piro was the mambo teacher, and he'd tell them `vaya' means `go.' Professional dancers would close the show, teachers from the Catskills: Mambo Bob, Killer Joe. Friday was the Hispanic hip crowd. The gamblers, the pimps, the numbers guys. They'd spend a lot of money, and the women dressed sharp. Saturday was the Hispanic crowd, but more the Puerto Rican crowd. And Sunday was the black crowd. That's just how it worked." Like so many artists who lived through the prime years of their art form, Mr. Palmieri takes a dim view of where Latin music has gone. "Back then, the dancers had a communication with the band. It was one on one. You'll never see it again. The art form, the tension and resistance, is gone. Every orchestra sounds the same. Nothing exciting." The writings of Schillinger, Mr. Palmieri said, taught him that music could be scientifically engineered to be thrilling; it is a matter of axes becoming balanced and unbalanced. "I don't guess I'm going to excite you with my music," he likes to say. "I know it." In summers during the early 60's, while Puente and Machito and Tito Rodriguez – the three heavies of the mambo – would take their bands up to the Catskills to play, Mr. Palmieri and La Perfecta would stay in New York playing four sets for $179.50 four nights a week, honing its raw, streetwise sound. Mr. Palmieri remembers it as pure pleasure. "There was a genius in that band," Mr. Palmieri said, "Barry Rogers, the trombonist. He and I had a thought transfer. I would change a riff, and he would catch up on it. There was always this movement, like the most organized jam session you could ever have." Rogers, who died in 1991, is the absent hero of the new La Perfecta. In the 1960's he arranged the particulars of the original music, after Mr. Palmieri sketched out the overall structure for them. He played with unusual force; on the old recordings he created a metal buzz that can be mistaken for overmodulation into the microphone. The old music, which had been lost, was retranscribed last year by Doug Beavers, a 25-year-old trombonist and master's degree candidate at the Manhattan School of Music. (He was brought to Mr. Palmieri by Conrad Herwig, who has been a trombonist in Mr. Palmieri's band for many years.) "Barry Rogers's sound characterized the band," Mr. Beavers said. "When he played, it was like 15 trombonists playing. And when you play that hard, you get a buzzing sound. On gigs he would play that way consistently. If your embouchure isn't set right, you won't get it. It's a study; it's a learned art." One of the Latin-music aficionados who was impressed by the band in the 1960's was Robert Farris Thompson, the Yale professor, scholar of African culture and author of "Flash of the Spirit," a widely respected book on the transmission of West African culture to the New World. In 1967, after many nights spent driving down from New Haven to stand in awe at the Palladium, Mr. Thompson wrote about Conjunto La Perfecta in The Saturday Review. "Palmieri and the members of his orchestra," he wrote presciently, "have demonstrated, in the sophistication of their stylistic means, the power to shift the course of Afro-Latin music forever." Professor Thompson is still at Yale, where beyond his teaching he serves as director of the Chubb Fellowships program. The awards are given four times a year and enable figures in politics and the arts to stay near the campus for several days, give lectures and interact with students. Last Monday Mr. Palmieri went to Yale for a class discussion, a banquet and a concert with La Perfecta. At the banquet Mr. Thompson delivered a panegyric. "You remind me of Aeneas," he intoned rapturously, "who lost Troy but found Rome. You closed the Palladium in 1966. And though we lost the Palladium, you found salsa. You teach us how to slice, drag, tease and release the beat, in the name of sabor. You teach us how to triumph over time." Mr. Palmieri beamed. Professor Thompson then introduced Snowboy, a disc jockey who presides over a Latin-jazz dance scene in London; he had brought eight dancers, traveling from England on their own dime, to perform for Mr. Palmieri. As Snowboy played some of Mr. Palmieri's most uptempo records of the 1960's, they danced powerfully in a wild mongrel style, a mixture of salsa, Brazilian capoeira, break dancing and swimming in breast strokes on the floor. Later at Woolsey Hall, a large chapel with a pipe organ, Mr. Palmieri gave a performance with La Perfecta. In some ways it was an unusually restrained concert; he didn't fashion many of the long, improvised keyboard preludes he's known for, which go out of tempo and into dissonant harmony. And where he usually shouts in guttural reflex while he plays, he was quiet at the keyboard. But in other ways the music took on a life of its own. Somehow the new Perfecta band, with three trombones, three percussionists, trumpet, flute, bass and piano and fronted by the singers Herman Olivera and Ray Viera, completely escapes the academicism of a repertory project. The music has been slightly rearranged, and the musicians are in thrall to it, blasting it out. Two powerful trombonists, Jimmy Bosch and Conrad Herwig, alternated in the dominant improvising role, the Barry Rogers role. As one soloed while the other grounded the brass in long tones, the sound bounced off the high ceiling of the chapel. Mr. Palmieri played, watching the design of the music unfold, his mouth open, his eyes shining.

|

----------

---------- ----------

----------