|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. THE NEW YORK TIMES Over 100 Years, The Williamsburg Bridge Has Diversified A Borough The Other Bridge, But All Brooklyn By JOSEPH BERGER June 22, 2003

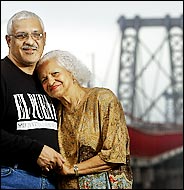

The Williamsburg Bridge opened in 1903. The family of Eugenio Maldonado, shown with his mother, Mercedes Ducos, came to Williamsburg in 1953 from Puerto Rico. It has often been pointed out that no great poem has been written to the Williamsburg Bridge like Hart Crane's ode to the Brooklyn Bridge, and that no one has ever tried to sell the Williamsburg to an out-of-town sucker. Yet in its long life as a workhorse, the Williamsburg Bridge has carved out its own distinct identity, and it is not a minor one. It is the Williamsburg Bridge that opened Brooklyn to the proletarian Jewish and Italian immigrants who had been crowded into the ghettoes of the Lower East Side, shaping the Brooklyn whose earthy charm endures today. These immigrants crossed the new bridge from their swarming tenements, moving into other tenements that might have had the small but precious advantage of a bathroom inside the apartment or a back alley instead of an air shaft. They took jobs along Williamsburg's waterfront, which was chockablock with refineries, foundries and warehouses. Yet the bridge, with its walkway to Delancey Street, allowed them to stay in touch with the relatives they left behind in Manhattan without the expense of a ferry. That history will be celebrated today, 100 years after the bridge opened, with speeches, stickball demonstrations, the cutting of a 10-foot cake big enough to feed thousands and the sounds of klezmer, merengue and the other music of those who came over the bridge to Brooklyn. ---------- The comedian Mel Brooks, born Melvin Kaminsky, grew up on Williamsburg's teeming South Third Street during the Depression. His mother was widowed when he was 2 and his older brothers, Irving, Lennie and Bernie, worked whatever jobs they could to pay the $16 rent for an apartment that faced the back. "There was," Mr. Brooks recalled, "a courageous family meeting around the porcelain kitchen table, and my mother said she was very depressed looking out in the backyard. `All I see are clotheslines and cats,' she said. `I want excitement. I want a better life.' She wanted to move to the front overlooking South Third Street." The neighborhood's inhabitants were ambitious (Mr. Brooks's family moved to the front for an extra $2 a month), and the bridge connected them to the more glamorous world uptown. It was over the bridge that Mr. Brooks's Uncle Joe took him in his cab to see his first Broadway show, "Anything Goes." "It was the road to the future," Mr. Brooks said of the bridge. He, of course, now has a hit Broadway musical himself. In the 1940's and 1950's, the bridge and its subway line opened Brooklyn to another set of newcomers – Puerto Ricans from the island or from crowded Manhattan – and in more recent years, the bridge has transported a group of aesthetic refugees, bohemian artists fleeing the day-tripper buzz of the East Village across the East River. In serving as this gateway, the bridge created some of New York's most flavorful neighborhoods. There are the streets filled with Yiddish-speaking Hasidim branching off clamorous Lee Avenue, the awning-shaded row houses and indolent cannoli cafes in the Italian enclave to the north, the domino players and Technicolor murals of the Puerto Rican Southside, the garage art galleries of the bohemian quarter along Bedford Avenue. The stately Brooklyn Bridge, which federal officials said last week had been a recent terrorist target, preceded the Williamsburg by 20 years. But it was not exactly an immigrant pathway because it connected Wall Street and City Hall with the somewhat elite Brooklyn Heights, said Dr. Kay Turner, a folklorist with the Brooklyn Arts Council. When the Williamsburg was built, it was the world's largest suspension bridge – 7,308 feet long with a main span of 1,600 feet. Looking like something put up by a very diligent boy with an Erector set, the Williamsburg was built for horse and carriage, but it soon carried trucks and subway trains. Williamsburg was then largely Irish and German. The Peter Luger Steak House had opened as a German establishment in 1887. Betty Smith sketched the neighborhood's poor Irish warren in her autobiographical novel, "A Tree Grows in Brooklyn," describing how 7-year-old Francie Nolan and her 6-year-old brother, Neeley, took baths together in a washtub in their railroad flat's kitchen and scavenged for pieces of junk to sell for pocket money. Within 10 years of the bridge's opening, the neighborhood's population had doubled to 250,000, and the better-off Irish and Germans began leaving. The Italian neighborhood to the northeast was close-knit. Everybody's parents and grandparents seemed to come from a few towns like Nola and Teggiano east of Naples. Anthony Bamonte, 63, remembered how the single phone booth in his family's 103-year-old restaurant, Bamonte's at 32 Withers Street, served as a lifeline to the outside world. "Nobody had phones," he said. "People used to call here, and we had to go across the street and holler to so and so to come. We used to go to 35, to 37, to 38. Sometimes we had to go up the block. You knew every family." While residents of other Italian neighborhoods have fled to suburbia, those of Williamsburg have stayed close to the bridge. Joseph Sciorra of the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute at Queens College, has lived on Devoe Street for 20 years and likes a place where he can have a fine meal at S. Cono's Pizzeria or pastries at Fortunato Brothers, started in 1976 by four brothers from a village near Nola. "I like the fact that it's still a neighborhood," Mr. Sciorra said. "If I don't have money on me at the local grocery store, the guy gives me credit till I come back next time. If I've forgotten something upstairs, I can leave my kids on the stoop and not worry." Eugenio Maldonado's family came right to Williamsburg from Puerto Rico in 1953 and settled in a tenement on South Fourth Street, close to where he now works as chief of operation at El Puente, a community organization whose name means "The Bridge." His mother, eager to save money, used to walk her brood of eight across the nearly mile-and-a-half-long bridge to buy clothing and school supplies along cheaper Delancey Street, bribing them with promises of ice cream. As they took in the bridge's cobweb of girders, the tar roofs and water towers of Williamsburg and Manhattan's skyscrapers, she talked to them "about how Manhattan was an island and that we came from an island," he recalled. Later, she peddled to her neighbors the sweaters and dresses she bought wholesale on Orchard Street on the Lower East Side. With her earnings, she opened her own tailoring shop. "The Hasidic community used to come to my mother's shop to turn the collars of their shirts when the collars used to wear off," he said. "They used to pay her 60 cents apiece." Luis Garden Acosta, El Puente's president, said that the bridge and the No. 6 train were the links that knitted together Puerto Rican families in Williamsburg, the Lower East Side, East Harlem and the South Bronx and gave them the political power of a single community. Mr. Garden Acosta's father used to take him to the colorful shops on Havemeyer Street, where Natan Borlam, an Auschwitz survivor from the former Czechoslovakia, opened a children's clothing shop in 1952. Mr. Borlam's son, Charles, said his father "figured that a neighborhood where people dressed up for Shabbos would be a good neighborhood to start a clothing shop in." Natan Borlam, who studies Torah commentaries between customers, now sells bar mitzvah and communion clothes at low prices to people from around the city and, through the Internet, in much of the country. But whenever the bridge has been shut for the reconstruction that has dragged on since 1988, he loses 30 percent of his business. As many Jews moved out to Queens or the suburbs, the only Jews left in Williamsburg seemed to be Hasidim, most of them followers of the Satmar dynasty. The first Satmar rebbe to stop in Williamsburg was Joel Teitelbaum, who came in the late 40's after spending time in the displaced persons camps with other Holocaust survivors. He chose Williamsburg to settle the remnants of his community because it had all the Orthodox necessities but was far enough away from the temptations of Manhattan. "He looked for a quiet community so he could restore shtetl life," said Rabbi David Niederman, president of United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg. In time, Rabbi Teitelbaum conducted tashlich – the Rosh Hashana service in which sins are ritually discarded into running water – from the bridge. "The Williamsburg Bridge was the symbol of our getting back our religious freedom," Rabbi Niederman said. Today Hasidim are regular users of the bridge's refurbished walkway. Alongside bicyclists and artists with pierced noses, Hasidic women push baby carriages on the walkway as their daily exercise. "It doesn't cost money, you can go anytime, and you don't need an instructor," said Annie Deutsch, who was taking a constitutional with her friend Rachel Friedman. Melting pot encounters, partly created by the bridge, have clearly reshaped the 128,000 people who now live in Williamsburg. They have brought conflicts, like those between the Hasidim and the Latinos over scarce housing. But they have also brought pleasures. Mr. Maldonado walks across the bridge to Manhattan just as he did when he was a child, but now he heads for Katz's Delicatessen and treats himself to a pastrami sandwich. "Then I walk back on the bridge and sweat it out," he said.

|

----------

----------