|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. THE NEW YORK TIMES In Two Shows, a New Latino Essence, Remixed and Redistilled By HOLLAND COTTER November 28, 2003

---------- For the Exit Art exhibition Milton Rosa-Ortiz used shards of glass to recreate a dress worn by Jennifer Lopez to the 2000 Grammy Awards. In art, as in fashion, old ideas rarely die. They just change shape and labels. Identity politics, a big feature of American art of the 1990's, is very over in the 2000's. Except that it isn't. It may look and sound different, less insistent and reductive, but for better and for worse it is still in operation. Two group exhibitions, one at Exit Art in Chelsea, the other at P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center in Queens, offer examples of the current model, or models. Both shows scrutinize something called Latino or Hispanic identity, an engrossing theme given the ever-expanding Spanish-speaking populations in the United States. But while one show jumps into the subject head-on and lands on its feet, the other drifts around above it and barely lands at all.

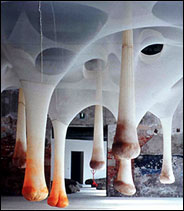

Exit Art advertises "L Factor" as a showcase for a generation of emerging artists who are redefining what Latino means, in part by being at a distance from it. Most of the artists were born in Latin America, but raised in the United States. Some speak no Spanish, or have names like Joskowicz, Kostianovsky and Schneider. Although they deal with symbols of Latino identity in their work, they themselves wear this identity loosely and lightly, as a personal choice rather than as an imperative. Unsurprisingly, in choosing their subject for the show, several of the youngish participants put dibs on currently hot cross-cultural stars: Jennifer Lopez is the subject of three portraits. At the same time, more culturally specific celebrities make an appearance, including some who bridge a generational divide, like the Mexican comedian Cantinflas, best known in the United States for his role in the 1956 film "Around the World in 80 Days." So do a few textbook historical figures who worked to secure a political power base for Latinos in North America. The utopian spirit of the educator Eugenio María de Hostos, for example, is honored by Iliana Emilia, an artist born in the Dominican Republic and living in Brooklyn, with a sculpture of a ship made of folded pages from school exercise books. And an artist who goes by the name of Johnny the Whip pays homage to the farm-worker organizer Cesar Chavez in a brown-skinned bust of the Statue of Liberty, balancing a head of lettuce on her torch. There is little question, though, that the most conspicuous source for the "Latinamericanization of United States culture" – I borrow the phrase from the art historian Gerardo Mosquera – is popular culture. And musicians, actors and athletes play a majority role in the Latino pantheon assembled at Exit Art. Celia Cruz – no one who heard her live could ever forget her – makes a posthumous splash in Xavier Tavera's photographs of a transvestite Cruz impersonator. An installation by the artist Felipe Mujica interweaves salsa with samples of contemporary sound art: Tito Puente's jazz-inflected rhythms combine with Stephen Vitiello's 1999 recording of the World Trade Center swaying in the wind to create a haunting New World music of the spheres. Nor is so-called high culture neglected in the show's mix. Christian Torres Roje offers a taped collage of two different recordings of a late Beethoven piano sonata as played by the Chilean musician Claudio Arrau, as well as a double bed on which visitors can do some laid-back listening. Arrau was a virtuoso in his field. So are Sammy Sosa and Roberto Clemente in theirs. Both make symbolic appearances here: Mr. Sosa in the form of a clear glass bat designed by Freddy Rodríguez, Clemente in a video by Eduardo Gil in which the baseball superstar miraculously levitates. Both pieces actually have a prickly undercurrent. The first refers to the recent uproar over Mr. Sosa's use of a bat containing cork, an illegal material. (Except for the one corked bat, for which Mr. Sosa served a seven-game suspension, the rest of his bats were cleared.) In the second, the airborne Clemente, who died in a plane crash in 1972, drops repeatedly to the ground. From entertainment and sports it is but a short step to art – taken here in Andrea Arroyo's portrait of Frida Kahlo as a set of gigantic black eyebrows – and from art to fashion. Valeria Cordero and Pilita Garcia Esquivel depict the clothes designer Carolina Herrera as a single immense black polka dot. Milton Rosa-Ortiz envisions Ms. Lopez in terms of the sheer, bejeweled dress she wore to the 2000 Grammy Awards, which he recreates from suspended shards of broken glass collected in the streets of the Bronx and on the beaches of Puerto Rico. Is this a political piece? I would say so, and one that links up in intricate ways with a portrait of another, earlier Latino diva, Lolita Lebron, the Puerto Rican nationalist who opened fire on the United States House of Representatives in 1954 and was imprisoned for 25 years. Her volatile spirit is distilled by Manuel Acevedo in a small cast sculpture of a perfume bottle in the shape of a pistol, an image in which sexual enticement and political incitement merge. Few such concisely provocative images turn up in "El real viaje Real/The Real Royal Trip" at P.S. 1, a smaller show (19 individual artists and a collective) spread over a lot more space, but generating far less energy. The title refers to Columbus's "discovery" of the Americas on expeditions bankrolled by the Spanish monarchy. And the exhibition – organized by the veteran Swiss-based curator Harald Szeemann, with Christian Dominguez and Jimena Blázquez, curators at P.S. 1 – purports to reveal a historically reflexive link between Spain and the Spanish-speaking Americas in art produced today. In fact, the show, with its puffy catalog, doesn't begin to fulfill this task, settling instead for being a mixed-bag showcase of 15 artists born in Spain, with one each from Costa Rica, Cuba, Mexico and Portuguese-speaking Brazil tossed in. The Brazilian Ernesto Neto, the best known of the group internationally, contributes an impressive example of his fragrant biomorphic sculptures made from pouches of stretchable fabric filled with herbs, spices and cloves. Arresting and less familiar is a performance-based video by Sergio Prego, who has a concurrent solo show at Lombard-Freid in Chelsea. But only three artists fully engage with the theme of cultural transaction implied by the title. Santiago Sierra, born in Madrid and living in Mexico, is one, with photographs of his own projects revolving around themes of immigration and dispossession. Another is Pilar Albarracin, who forges a trans-Mediterranean connection in an installation titled "The Trip: Habibi." Set outdoors in P.S. 1's courtyard it consists of a beat-up and frantically bucking Mercedes piled high with the luggage of North African migrants. The strongest piece by far, though, is an installation by Tania Bruguera, an artist born in Cuba and now living in Chicago. Titled "Autobiografia," it lures the visitor down a long, narrow corridor filled with the sound of voices repeating political slogans from the Cuban revolution, and into a small pitch-black space pulsating with inchoate noise. Not recommended for anyone prone to claustrophobia, it constitutes an intense physical and psychological trip on its own. It's too bad that "The Real Royal Trip" didn't follow Ms. Bruguera's propulsive lead and concentrate on dramatizing and disrupting the very notion of identity politics, which has, after all, always been fraught with problems. By the time it finally caught on in mainstream New York art in the 1990's, artists who stood to gain attention from it, Latinos among them, were already seeing it as just the latest way to corral them into a manipulable, if temporarily marketable, outsider corner. In fact, this is pretty much what has happened, leaving certain careers stranded now that the fashion parade has moved on. At the same time, that parade hasn't moved all that far and it has picked up all kinds of new traffic. As "L Factor" demonstrates, something called Latino identity – repackaged, rethought, refined – remains a source of stupendous vitality within a bigger something called American culture. And the P.S. 1 show, while missing the boat in essential ways, at least makes the point that every cultural trip, far from ending in the historic past, is always beginning in the here-and-now, wherever, whenever that may be. ********** "L Factor'' is at Exit Art, 10th Ave nue at 36th Street, Chelsea, (212)966- 7745, through Feb. 15. ``El real viaje Real/The Real Royal Trip'' is at P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center/MoMA, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, at 46th Ave nue, Long Island City, Queens, (718)784-2084, through Jan. 5.

|

PHOTOS: Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

PHOTOS: Tanya Bonakdar Gallery "L Factor" at Exit Art is a classic example of the kind of eclectic, rough-around-the-edges, slightly larger-than-life show that this nonprofit space has been doing for 20 years. As is often the case with these projects, chance played a curatorial role. Papo Colo and Jeanette Ingberman, Exit Art's co-directors, came up with the idea for a Latino show, and specifically a show of "conceptual portraits" of influential Latino cultural figures. They then solicited proposals for work through a mass e-mailing; from some 300 responses, they selected 30 artists.

"L Factor" at Exit Art is a classic example of the kind of eclectic, rough-around-the-edges, slightly larger-than-life show that this nonprofit space has been doing for 20 years. As is often the case with these projects, chance played a curatorial role. Papo Colo and Jeanette Ingberman, Exit Art's co-directors, came up with the idea for a Latino show, and specifically a show of "conceptual portraits" of influential Latino cultural figures. They then solicited proposals for work through a mass e-mailing; from some 300 responses, they selected 30 artists.