|

|

|

Esta página no está disponible en español. THE NEW YORK TIMES At 40-Year Bronx Beach Party, Who Needs Sand? By DAVID GONZALEZ August 7, 2004

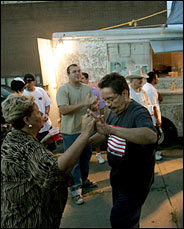

Sarah Ortiz singing for a crowd at Primitivo Marty's truck/kitchen- on Viele Ave. in Hunts Point dances with Marty PHOTO: James Estrin/The New York Times Two old guitarists sat on folding chairs, eyes closed and heads back, singing of heartbreak and homesickness - the kind of dreamy boleros they first crooned when their hair was dark and their hopes were bright. Nearby, younger revelers swirled and shimmied to classic salsa, their dips punctuated by tight horn flourishes. Beach towels hung on fences, and the air was thick with the sweet aroma of codfish fritters sizzling in oil. The sight of the Puerto Rican flag flapping in the wind made the hearts of many of that island's sons and daughters flutter a bit faster here at La Playita, the Little Beach. Despite its name, it is neither little nor beachy nor, for that matter, even in Puerto Rico - unless the Bronx has been secretly annexed to the island. Yet every summer weekend for more than four decades, thousands of people intent on recreating a slice of tropical life transform a stretch of factories and dumps along Viele Avenue in Hunts Point into an unlikely oasis that is perhaps the city's least-known but longest-running weekend street party. Cheaper and closer than Orchard Beach or Van Cortlandt Park, the loose and loud strip has enticed generations of nostalgic islanders pining for sun and space amid bricks and asphalt.

Centerdancing to music in front of his truck/kitchen- on Viele Ave. in Hunts Point - Here he dances with a singer known as Hilda PHOTO: James Estrin/The New York Times "I come here for the culture," said Lorenzo Rodriguez, a musician who visits as much to relax as to play guitar. "We remember our islands, where we always got together on Saturdays in the park. The fried food. The music. Above all, the friends, always the friends. It's like a dream to be closer to the tropics." But life has hardly been tranquil at the Little Beach. Those who started it feel they have been shunted aside. There have been accusations, and recriminations. What started out as a low-key get-together of friends who played dominoes and listened to the old songs has turned into a noisy, bustling festival, with dozens of unlicensed vendors who settled there after being kicked out of parks and lots elsewhere in the borough. And while the strip has a reputation for being a safe destination for families, the police briefly closed it down last month when one partygoer tossed a piña colada at the commanding officer of the local precinct. The dust-up prompted the newcomers to organize themselves and to apologize to the police, who, in turn, have allowed the party to continue. But now there are stricter patrols, to stop double-parking, speeding motorcyclists and under-the-table liquor sales. Norma Ruiz, a food vendor who trooped into the 41st Precinct station house a few weeks ago to ask for a second chance for herself and 39 other vendors after the piña colada incident, said the real danger was too much competition and bickering among vendors. "They don't understand the sun shines for us all," she said. "If someone is selling near me, we are both lucky to make a few dollars. We are not here to be become millionaires. We're just here to get out a little bit from our problems." Like many of the vendors here, she first came to enjoy the music. She remembers trekking to the end of Tiffany Street with her husband, Gilberto, to while away a few weekend hours listening to the romantic songs. It was the late 1960's, a time when the borough's southern tip was about to be cursed by Jobian misery. "There was live music," she said. "I would dance with my husband. He would put his slippers in his pockets and dance barefoot." "That was when I used to drink," he chimed in. That was also when Primitivo Marty ruled that end of La Playita. He, along with Rey Lopez, are considered the pioneers who staked out the area during the 1960's. Mr. Marty, who is known to all as Pitito, had sold his restaurant on Evergreen Avenue and bought a bread truck, which he turned into a cafeteria on wheels that served food to the factories in the area. A half mile on the other end of Viele Avenue, Mr. Lopez, a former boxer, was doing the same. They soon had the idea of inviting musicians to play by their trucks on the weekends, more for atmosphere than business, though it did not hurt sales. Pitito called his corner, at the western end of Viele Avenue, Villa Brisas del Mar - Sea Breezes Villa - though all it faced was the East River and a wooden shack on an otherwise vacant lot he used as an improvised stage. There were no palm trees, but he did plant two saplings that once fit in the palm of his hand. "They were the size of a tallboy," he joked, referring to a large-size can of beer. "Now look at them." Look is all he can do, since the city fenced off the lot several years ago for what will one day be a public park. The two trees now tower more than 40 feet over the lot, though the only shade Pitito enjoys is from a tarp by his truck. He wound up parking near the lot after an invasion of newcomers - people who, unlike him, have no licenses and pay no taxes, he said - pushed him off the strip. He now says that until things calm down a bit, he will hold off inviting any more musicians to play for his customers. Besides, no one can hear anything with all the radios blaring away. "When this was only Rey and Pitito, this was the best," said Edelmira Carrero, who was disappointed to learn there would be no live music last weekend. "It changed when all these people got in here." By most accounts, the newcomers starting setting up their tents and tables about two years ago. Some had been evicted from Crotona Park, others from another parcel called Villa Cuernos, near Third Avenue and 156th Street. The police said the tensions first surfaced a couple of months ago. "What is happening is the younger group is trying to overtake the older group," said Capt. Richard Kazman, executive officer of the 41st Precinct. "We don't want any problems. But as far as I was told, if anything is out of control, the inspector is going to shut everybody down." Many of the new vendors admit that they neither pay taxes nor have licenses. Ms. Ruiz said she had permission from the police and the local community board to have a street festival every weekend until Sept. 12. Local officials, however, said the permit had yet to be approved and that it would only be good for one day. Still, the police appeared to be tolerant, if vigilant, as long as people behaved. Despite the crowds and the noise, the mood on the strip was relaxed when it reopened two weekends ago. A man sat Buddha-like, his skin glistening with suntan oil, while he dozed on a beach chair. Near Casanova Street, Augusto Hernandez and his friends indulged in some reverse karaoke. He played the flashy flourishes on his timbales while his friends beat on conga drums, accompanying a recording of Hector Lavoe singing "El Todopoderoso." Vivian Serra, her son and a friend chatted on one corner, playfully spraying each other with cooling mists of water. A few feet away, a D. J. was setting up a sound system whose speakers dwarfed most cars. "I enjoy watching the oddities, the ones who come here like it's Saturday night at the club," Ms. Serra said. "The women in heels and short dresses and their hair done up to the nines. What are they looking for? I'm not going to judge. But it's Saturday afternoon in the park, not Saturday night at the club!" It is anything but a walk in the park for the vendors. Many of them sell the same things, especially those who hawk down-home delicacies like roast pork, fried empanadas and rice with pigeon peas. Ivelisse De La Cruz no longer brings a tire-size casserole full of rice. A small pot will do. "It's getting bad," she said. "My customers used to run over like ants and buy everything. Now I have leftovers and lose money. This used to just be from the block, but now we get a lot of people from other places" selling food. Luz Rivera is on her second summer at La Playita, selling $15 pairs of sneakers adorned with the Puerto Rican flag. Like other vendors, she sometimes has her children help her. "They know if their mother and father are making honest money here they can do it," said Ms. Rivera, a school aide. "We parents make money the hard way. We work. I bring my two sons here to see what I go through. I'm making the sacrifice so they can go to college." Near Rey Lopez's truck, half a mile away, sacrifice was also on Annette Santiago's mind. She used to come here 30 years ago as a child, when her grandfather Diego Pagan would join Rey in song. She lived in Florida for a while, but came back to New York several years ago to get better care for her daughter, who has cerebral palsy. "They gave me the strength to be the mother I had to be," she said of Rey and her grandfather. "They gave me inspiration. They used to make up songs about me. He struggled so much so the kids could go to school." Her grandfather is dead. But Rey still reigns in his truck, an old boxer whose fast hands now flip burgers and chop pork. Every now and then he let out a few lyrics in tune with the music blaring from the radio. On his truck, faded photos of boxers and balladeers covered every inch. "They always made me cry, those songs," she said. "But my grandfather lives in me. He lives in the music. For my kid, one day this will remind her of me."

|

__________

__________ __________

__________